Note

The texts of the exhibition were written until 2009. Since then, there have been no systematically additions. Regarding younger developements in the field of homeopathy the information given might not represent the actual state.

Homoeopathy Worldwide

Still in Hahnemann’s lifetime, homoeopathy became known beyond the borders of Germany. Translations of his main writings, personal contact among homoeopathic physicians and a cosmopolitan clientele played a major part in this expansion.

Today Hahnemann’s approach to healing is represented in many countries worldwide and is often officially included in a country’s public health system.

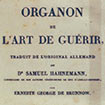

This development was strongly driven by Samuel Hahnemann’s main work Organon of the Healing Art (1810). By the 1830s it had been translated into several other languages. It thus became known internationally which was quite unusual for a scientific publication at the time.

The world history of homoeopathy can be divided into three phases: rise and consolidation up to c. 1900; stagnation and decline up to c. 1970; then renaissance. Europe was dominant up to the 1860s. After that the homoeopaths in the USA became more active. Since the 1970s India and Latin America have gained increasing importance. At the same time homoeopathy is also experiencing a revival in Europe and the USA.

The dissemination of homoeopathy in France was promoted by Hahnemann’s Paris practice which he maintained from 1835 up to his death in 1843. At the same time Sébastien des Guidi (1769 – 1863) made homoeopathy known among the French medical fraternity. In the 19th century the supporters of homoeopathy included noblemen, clergymen and intellectuals. Some of them regarded it as a welcome alternative to the materialism of orthodox medicine.

In Paris, Bordeaux and Lyon physicians tested the new healing method in clinical trials. After 1871 homoeopaths founded their own hospitals in Paris and Lyon. In polyclinics in Paris, Marseille, Bordeaux and Nantes more than 100,000 patients were seen per year as early as 1865 which strongly contributed to the dissemination of homoeopathy.

Before World War I Léon Vannier (1880 – 1963) took the first steps towards overcoming the fragmentation in the homoeopathic field: he founded a journal to promote consensus within the doctrine, organized structured tuition, improved the manufacture and sales of remedies and supported further research. From the 1930s competing establishments also aimed at integrating homoeopathy into scientific medicine and the market. The fusion of several manufacturers in 1967 led to the foundation of the Boiron company which has become world leader for homoeopathic medicines.

The French national health system acknowledged homoeopathy in 1965 and has paid for medicines and treatment until 2021. France is Europe’s biggest market for homoeopathic medicines. While they were used by 22 % of the French population at least once in 1984, the percentage has since risen to more than double that figure. French homoeopaths were also crucial in introducing the method in Brazil and, since the 1970s, also in promoting the training of physicians.

In Great Britain there have been practising homoeopathic physicians since the 1830s. The Royal family has sought homoeopathic treatment since the 19th century and advocates the approach publicly, thus securing for it a high reputation in society.

The first hospital was founded in London in 1842 by the silk merchant William Leaf (1791 – 1874). Its competitor, the London Homoeopathic Hospital, which goes back to an initiative of the physician Frederick Quin (1799 – 1878) admitted its first patients in 1850. Quin was a pupil of Hahnemann’s. Also in the early 1840s, the first successful clinical trials were carried out in Edinburgh and elsewhere. By 1846 there were 12 polyclinics in the United Kingdom; by 1853 the number had grown to 57.

The majority of homoeopaths preferred low potencies which can be seen as a rapprochement to orthodox medicine. The decline of homoeopathy first became tangible in the 1880s. Giving preference to high potencies was to underline the distinctiveness of homoeopathy. John H. Clarke (1853 – 1931) promoted the reception of the work of James Tyler Kent (1849 – 1916) who, among other things, emphasized the metaphysical aspects of homoeopathy. Clarke trained many lay practitioners, among them Noel G. Puddephatt (1899 – 1971) who was the teacher of the now famous George Vithoulkas (born 1932).

After World War II homoeopathy was incorporated into the National Health Service (NHS). Since 1950 it has been acknowledged as a medical specialization. Until 2017, the NHS has been paying for homoeopathic treatment. This circumstance has permitted systematic research into homoeopathy in several NHS out-patient units since the 1980s. The Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital is a flagship for homoeopathy in the United Kingdom. Since 2010, it is called Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine. It is seen as a research and education center, specialising in chronic medical conditions. Their services include homoeopathy, behavioural therapy, manual medicine service, acupuncture, hypnosis and others.

In Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, Spain, Italy and Greece homoeopathy has long been widespread. Its position in Scandinavia is relatively weak in comparison. In some Central European countries such as Hungary and Poland, as well as in Russia and Ukraine, it is presently experiencing a renaissance.

The Habsburg Military promoted homoeopathic research in occupied Italy with first clinical trials being carried out in Naples in the 1820s. As a result the Organon was translated into Italian. Especially in the 1990s Austria organized many courses in Central and Eastern Europe.

In Hungary, homoeopathy found supporters early on, among them none less than the national hero István Széchenyi (1791 – 1860). Two university chairs were appointed in Pest in 1871 and 1873. At the time they were unique in Europe. The Hungarian example was also discussed in Germany. Where there had been a number of hospitals before, only one homoeopathic ward was left in the 1930s, at the Elisabeth Hospital in Budapest under the direction of Gustav Schimert (1877 – 1955).

In Russia, German physicians (e.g. Schweikert junior and senior) brought homoeopathy to the attention of the Tsar and the aristocracy. This clientele made sure that there were homoeopathic physicians in the army and the navy, later also with the state railways and in hospitals. Despite the restrictions imposed by the Soviet Union, some clinical trials were permitted in the 1950s. Polyclinics flourished in Moscow and other metropolises. Some leading party members were treated homoeopathically. In the 1980s homoeopathy was more openly tolerated and, in 1991, it gained state recognition in Russia and the Ukraine.

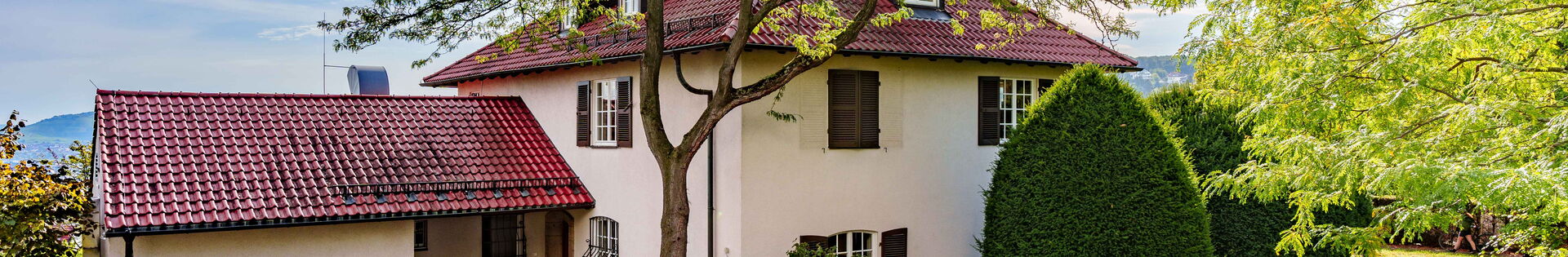

The Swiss homoeopaths were crucial for all of Europe in the 20th century. The Genevan physician Pierre Schmidt (1894 – 1987) studied classical homoeopathy in the USA and made it known especially in the francophone countries and Italy from the 1950s onwards. In the German speaking countries the same was achieved by the Swiss physicians Adolf Voegeli (1898 – 1993) and Jost Künzli von Fimmelsberg (1915 – 1992). Rudolf Flury (1903 – 1977) rediscovered the LM potencies already in 1942 and was the first homoeopath to produce them again since Hahnemann.

The European homoeopathic physicians joined forces in 1990 by founding the European Committee for Homoeopathy (ECH) to represent their interests in Brussels: the unrestricted practice of homoeopathy by physicians and a unified, high standard of training. In 1999 the manufacturers of homoeopathic and anthroposophic medicines united under the name ECHAMP (European Coalition on Homoeopathic and Anthroposophic Medicinal Products) to secure easier access to these medicines on a European level.

It was mostly due to immigrants that homoeopathy became known in the USA in the 1830s. Soon it presented a serious competition for orthodox medicine. In the last third of the 19th century 7 % of all physicians were homoeopaths. The pharmaceutical manufacturers Boericke & Tafel operated worldwide.

American homoeopaths were particularly successful in the field of training. As early as 1835, Constantin Hering (1800 – 1880), an immigrant from Saxony in Germany, founded the first homoeopathic academy in Allentown/Pennsylvania. By 1860 there were five colleges; big clinics were added later on. In the USA important clinical trials were carried out. The strongly scientific orientation led to a loss of identity for homoeopathy and to its marginalization after the turn of the century.

James Tyler Kent (1849 – 1916) worked against this trend by emphasizing the distinctiveness of homoeopathy. He preferred strongly diluted medicines and, in 1897, he created a repertory which is still in worldwide use today. In the long term, American lay literature also made an impact, for example Hering’s introduction to homoeopathy, the Homoeopathic Domestic Physician which was first published in Philadelphia in 1837 and saw many new editions as well as translations. It was still translated into Spanish in 1923. Since the 1980s American homoeopathy has been experiencing a renaissance which, this time, started at the West coast and is mostly carried by lay healers.

In some Central and South American countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay homoeopathy looks back on a long and consistent tradition. It was the Spanish physician Cornelio Andrade y Baz who introduced homoeopathy in Mexico in 1849. As early as 1854 it gained state recognition after a yellow fever epidemic. A physician’s association and a journal were founded in 1861 and, in 1871, a homoeopathic hospital was set up which still operates today.

In other countries the number of homoeopaths picked up again after a first flourishing period, such as in Chile or Bolivia, or after disruptions,as in Cuba, and rose steadily during the last third of the 20th century. Since 1992, homoeopathy has enjoyed systematic support in Cuba. It is now part of the state health service and thus widespread in the entire country. In that region, homoeopathy is at least state-recognized in many countries which means its practice is permitted as a medical method, the training is accepted as a medical specialization or its remedies are officially registered and therefore form part of the pharmaceutical training.

In the 19th century many Latin Americans studied in the USA. But in the first decades of the 20th century a national school was founded in Mexico which gained fame beyond the borders of Latin America in the second half of the century through Proceso Sánchez Ortega (1919 – 2005). The Argentinean physicians Tomas P. Paschero (1904 – 1986) and Alfonso Masi-Elizalde (1932 – 2003) also achieved international acclaim.

In Brazil homoeopathy has had an ongoing tradition since 1810. At the beginning it was mostly spread by the Frenchman Benoît Mure (1809 – 1858) who immigrated to Brazil in 1840 and founded a homoeopathic training institute for physicians and lay healers (!) in Rio de Janeiro in 1843. A competing foundation where only physicians could train brought to expression the division among homoeopaths. In 1912 the state recognized, academic Faculdade Hahnemannia opened and was extended, in 1916, by a clinic of 200 beds. Up to 1965 homoeopathy remained a compulsory subject at the medical school in Rio de Janeiro.

In the 1930s and 1940s, radio and press regularly broadcasted information about homoeopathy. Since 1926 national homoeopathic congresses have taken place, which were initiated by José E. Rodrigues Galhardo (1876 – 1942). It was only in 1979 that this vast country set up its first national physicians’ association (AMHB).

Since 1977 homoeopathy has been officially recognized in the pharmaceutical, since 1979 also in the medical field. Homoeopathic physicians and pharmacists have a particularly close relationship in Brazil. Today homoeopathy is fully integrated in the state health system (SUS) which has the task to secure health care for the whole population. With c. 4 % of physicians being homoeopaths Brazil has one of the highest percentages worldwide.

In the Asian region, India and Pakistan are the geographical focus point for homoeopathy. It was introduced in the first half of the 19th century by European physicians. Soon, native doctors and lay healers also developed an interest in homoeopathy as its concepts were easily reconcilable with traditional Indian healing approaches. At the same time it was seen as modern Western medicine. The fact that it does not rely on ‘strong’ drugs made it particularly popular.

Bengal became the geographical centre of homoeopathy in India. Its capital Calcutta featured most of the training institutes, pharmacies and publishing houses. From there, homoeopathy spread especially to the North in the 20th century. On the South Indian coast, local centres had been founded already in colonial times, partly by missionaries, more often due to the cooperation between British state officials and Indian physicians.

In 1937 the Central Legislative Assembly of India first accepted homoeopathy. Since 1973 it has enjoyed full public recognition. Just like Ayurveda and other Indian medical systems, it is organized by the state as an independent discipline next to orthodox medicine. Within this framework, the homoeopaths make their own decisions with regard to their register of physicians, training standards and accreditation of the almost 200 medical schools. Homoeopathic physicians work as part of the national health system, for example in primary care. They operate 230 hospitals of their own. More than 20 national institutes carry out homoeopathic research including the proving of Indian active substances. Homoeopathy has also been used for decades for the prevention and treatment of epidemics.

The 154,000 homoeopaths (as of 2007) make up 13.4 % of all Indian physicians. This is the highest percentage worldwide. Over and above that, there are 66,000 not academically trained, but registered homoeopaths who are particularly important in providing health care for the poor. Here, homoeopathy proves to be especially effective, economic and relatively easy to use.

After gaining independence India developed into an internationally highly acclaimed centre for homoeopathy. Physicians from all over the world have travelled there for decades to gain work experience because homoeopathy is used for many more disease pictures in Southern Asia than, for instance, in Europe. What is also special is the seasonal use of remedies which takes into account the country’s climatic conditions.

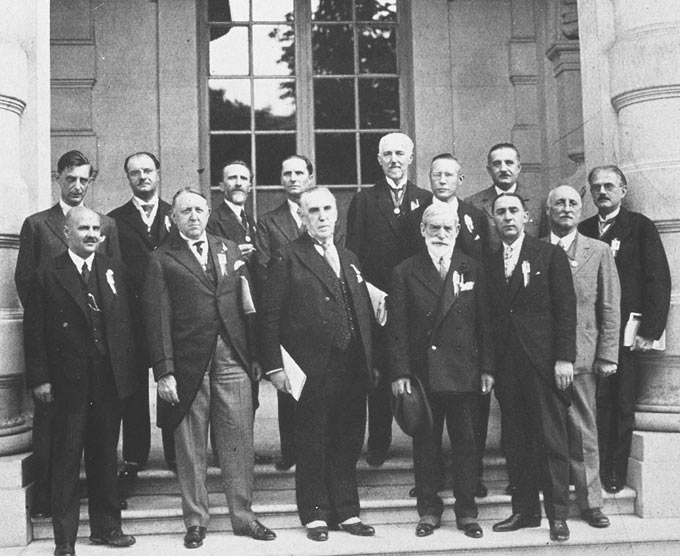

Since 1876 international congresses of homoeopathic physicians have taken place regularly every five years, alternating between the USA, Great Britain and France. Only in 1925, an official worldwide alliance was set up in Rotterdam: the Liga Medicorum Homoeopathica Internationalis (LMHI) which has organized annual congresses since then. Conferences have also taken place since 1929 in Central America (Mexico), since 1967 in India (New Delhi) and since 1971 in South America (Buenos Aires). Now, every third congress takes place outside Europe or the USA which is a sign for the growing importance of the emerging homoeopathic markets. At the congresses, several thousands of physicians come together from all over the world, which means that the global exchange of knowledge is greatly accelerated.